Unless the glue of power keeps it together, there is a distinct possibility of the Islamist militia falling apart, given its internal differences

Ever since the Taliban established their sway over Afghanistan in 1996, the question that has remained a persistent background whisper is whether their regime would last, and for how long. The speculation has been whether their Government would implode from with in, or would be undermined by violent opposition by organisations like the Islamic State of Khorasan or would collapse thanks to both.

As to the first, it has been known for a little over two decades that the Taliban, formed in April 1994 in southern Afghanistan, has had internal differences and contending factions. Steve Coll, in Directorate S: The CIA and America’s Secret Wars in Afghanistan and Pakistan, 2001-2016, cites CIA deputy director John McLaughlin as saying the organisation’s analysts had reported to President George Bush Jr’s cabinet in 2001 that the “Taliban is not a monolithic organisation”. Their assessment was, “There are ideological adherents but many others are with them because it is how you get money and guns.” Coll goes on to say, that it followed logically from this conclusion that there had “to be a way to drive wedges in the organisation”.

The CIA, according to Coll, had identified individuals in the Taliban leadership who claimed that they disagreed with the Taliban’s supreme commander Mullah Mohammad Omar’s provision of sanctuary to Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda because harbouring terrorists deprived the fundamentalist Islamist militia of international recognition. If, however, there was dissent within the Taliban, it did not lead to any breach even after the US-led war that began on October 7, 2001, led to their ouster from Afghanistan by mid-December.

That there was factional tension, was indicated by the idea of there being “good” and “bad” Taliban, the former being people with whom the US and other countries could fruitfully engage in talks. The first proponent of the idea was clearly Pakistan which sought to sell it to President George Bush Jr’s administration in the aftermath of the September 11, 2001, terror attacks on the World Trade Centre and the Pentagon’s E-Wing. It did not have any practical consequences. Mullah Mohammad Omar, the first Ameer-ul-Momineen (translated as Supreme Commander of the Faithful) of the Taliban, refused to hand over Osama bin Laden and his associates and evict al-Qaeda from Afghanistan.

The idea, however, continued to circulate and had subscribers like Hamid Karzai, Afghanistan’s President from December 22, 2001, to September 20, 2014. A section of the Taliban, including Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, a co-founder of the Islamist militia, and now one of the three Deputy Prime Ministers in the Taliban Government, was viewed as one of them. Nothing came of it as the Bush administration rejected the idea. Karzai, however, continued reaching out to the Taliban with Mullah Abdul Salam Zaeef, former Taliban Foreign Minister, leading efforts on his behalf to persuade the Taliban to negotiate an end to the war. His brother, Ahmed Wali Karzai, also had indirect contacts with Mullah Baradar.

Mullah Baradar’s arrest in January 2010 and interrogation by the Pakistanis and, subsequently, Americans, put paid to the backchannel talks the Americans and Karzai’s Government were having with a section of the Taliban. Indeed, the arrest was clearly a result of Islamabad’s move to scuttle the talks, particularly those between the US and the Taliban, which were being conducted without it being kept in the loop, a fact it deeply resented.

In a report datelined February 16, 2010, and titled “Taliban Arrest May be Crucial for Pakistanis”, in The New York Times, Carlotta Gall and Souad Mekhennet say that Baradar’s arrest came at a delicate time when the Taliban were in a fierce internal debate about whether to negotiate for peace or fight on as the US prepared to send 30,000 more troops to Afghanistan as a part of President Barack Obama’s strategy of launching a new offensive later in the year. It cited a member of the Kandahar provincial council, Haji Muhammad Ehsan, saying that while some hardliners argued in favour of continuing the fight, the balance had been shifting increasingly in favour of negotiated peace.

The differences within the Taliban continued with strategic differences intertwined with ethnic and regional allegiances and personal ambitions. The factional contestations emerged in sharp focus in 2015 when it came to be known that Mullah Omar had died on April 13, 2013, but the fact was kept a secret and Mullah Akhtar Mansour ran the organisation in his name. Mansour, who became the successor in July 2015, was killed by a US drone strike on May 21, 2016, following which Sheikh Haibatullah Akhaundzada became the Ameer-ul-Momineen.

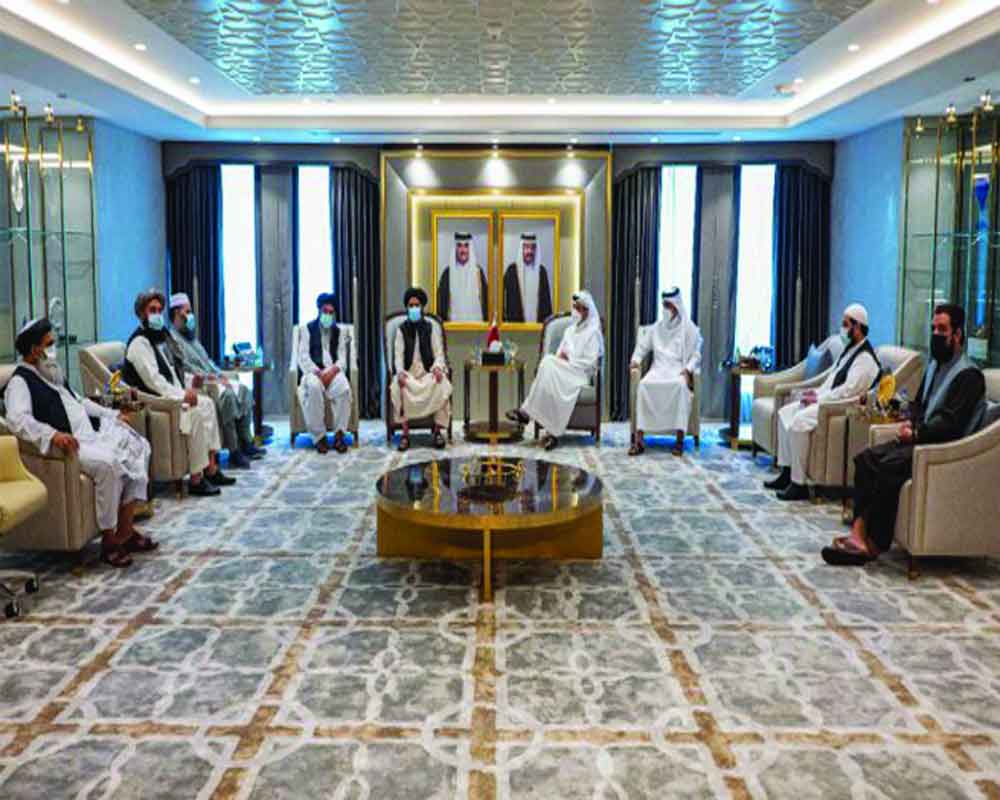

The continuing factional tussles intensified sharply during the exercise in Government formation that followed the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan. The country’s capital, Kabul, fell to them on August 15, 2021. It took them three weeks thereafter to announce the first list of interim — not permanent — Ministers. The composition of the Ministry and the subsequent expansions clearly reflect an effort to reconcile conflicting claims for ministerial berths. With the passing of time, issues like those of human rights, particularly those of women, and inclusive Government, on which sharp differences exist, will further aggravate matters. Will the Taliban Government implode? It is difficult to tell. Power is a glue that can stick polar opposites together.

(The author is Consulting Editor, The Pioneer. The views expressed are personal.